.HOME |

Be sure and note what a limited waiver of sovereign immunity looks like! |

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

USAO 2883 Indian Studies Southern Plains Leadership |

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

Instructors: Megan Benson and J.T. Goombi USAO-Anadarko (Anadarko Public Schools Indian Education Center) Questions? Call 405 364-1144 email: benson.megan@gmail.com goombifornow@yahoo.com website: meganbenson.com Course description: Class will examine topics of importance for modern tribal leaders, future leaders, and for those who want to participate knowledgeably in tribal decision making. Topics include: The nature of modern tribal sovereignty Where is Indian Country? Natural resource control and development The Winters Doctrine--Indian Reserved Water Rights in the southern plains context Environmental programs and concerns Housing Economic development possibilities using the 1936 Oklahoma General Welfare Act |

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

Reading material consists of printouts available at the USAO bookstore Class schedule: (see adjustments and new addtions below) January 5 Introductions and explanation of course material Historical background: treaties, trust, and sovereignty January 12: assignment: give a short summary of what is located at each web link on this page; discussion will include hisotrical context of tribal sovereignty January 19: Continuing discussion of historical context: Reading assignment--Treaties that are relevant to your specific tribe or one you are interested in. Write a short summary of each treaty and any thoughts you have on what those treaties mean to you today. January 26: What is Indian Country? Where is it? Who is it? Read court cases Pottawatomi and Sac and Fox (links here). Write a brief summary of your definition of Indian Country in Oklahoma today. February 2: Read the editorial of One Nation and write a short discussion of what One Nation thinks and how you would refute the editorial. February 9: Reexamining the Indian Reorganization Act and the Oklahoma General Welfare Act. Read the two acts linked below. Class discussion on constitutions and corporate charters; what they are; why they are important. February 16: Kiowa Constitution: midterm project and paper. Read five tribal constitutions and in a 3 page paper compare and contrast them. Due March 1. Read also the article on Indian law linked below. February 23: Kiowa Law and Status. Come prepared to discuss how Kiowa traditions mght be incorporated into a "constitution." March 1: Indian Reserved Water Rights: what does the Winters Doctrine mean to the tribes of the southern plains. Open lecture. Everyone welcome: read Winters v. US See also the NYT article on west Texas water. Begin to plan papers and the publication of "Tribal Leadership Symposium Position Papers: 2004." March 8: Environmental programs; EPA and the nature of sovereignty. March 15: Spring Break! March 22:discussion of papers. You will need to do a 5 page paper on one of the areas we have discussed. We hope you can find one that is personally relevant. Incorporate your own experience and prepare to give a short presentation of you paper in class along with a written version for your grade. March 29: Class will meet at the University of Oklahoma Law School Library, Norman. You will have an opportunity to do some research on your paper topic. April 5 and 12: Papers and discussion: turn in papers on April 5. They should be typed 12 Times New Roman. They should have a strong thesis statement that clearly states your case. We will discuss paper writing. You will present your research for the whole class. |

Click on map to enlarge |

Legislation |

Treaties |

Oklahoma's Indian Disclaimer: ENABLING ACT Act of Congress, June 16, 1906 34 U.S. St. at Large, pp. 267-278 Section 1: That the inhabitants of all that part of the area of the United States now constituting the Territory of Oklahoma and the Indian Territory, as at present described, may adopt a constitution and become the State of Oklahoma, as hereinafter provided: Provided, that nothing contained in the said constitution shall be construed to limit or impair the rights of persons or property pertaining to the Indians of said Territories (so long as such rights shall remain unextinguished) or to limit or affect the authority of the Government of the United States to make any law or regulation respecting such Indians, their lands, property or other rights by treaties, agreements, law, or otherwise, which it would have been competent to make if this Act had never been passed. |

">

">

">

">

Links |

Case Law |

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

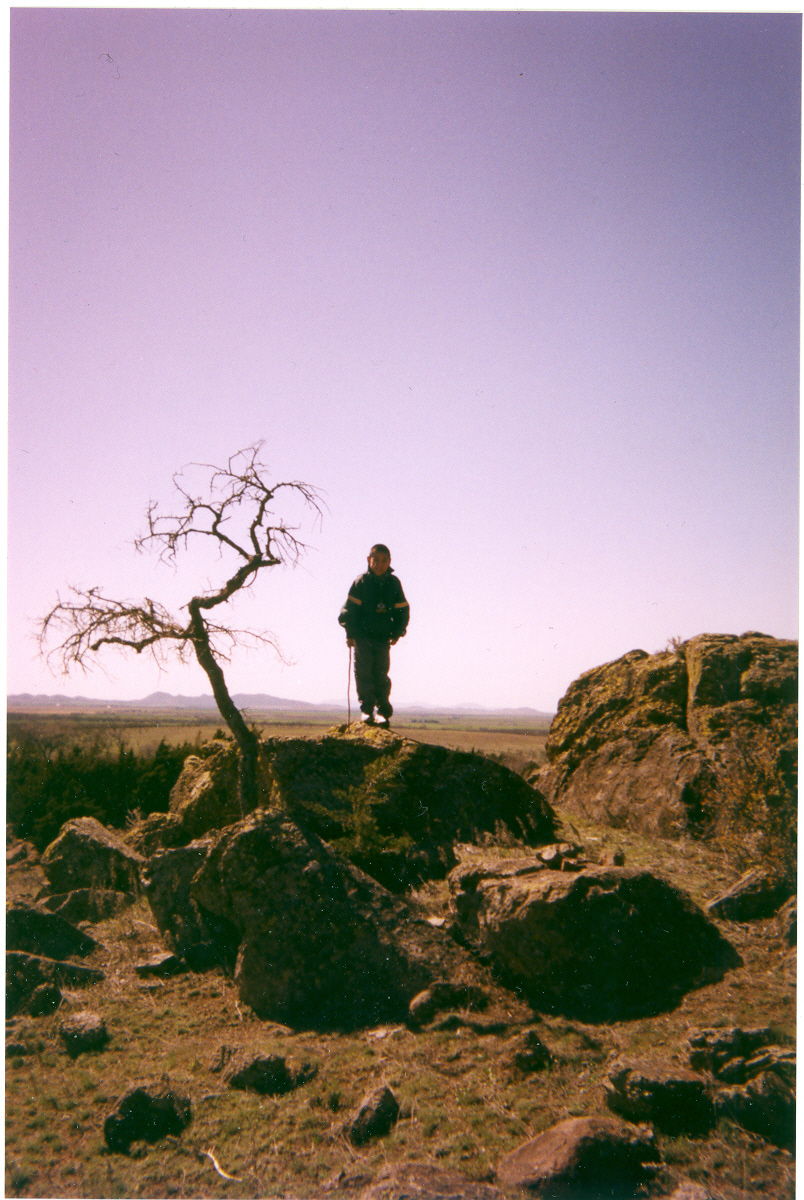

Ian Autaubo with the Kiowa Clemente class at Cutthroat Gap. Ian is an heir to the original allottee of this land. |

J.T. Goombi |

"TO SERVE THE FUTURE HOUR.." |

Be sure and note what a limited waiver of sovereign immunity looks like! |

">

">

">

">

Even more exciting links ! |

">

">

">

">

Important Gaming Links |

Summary: Indian Reserved Water Rights -Megan Benson, Ph.D. All federal land reserves (national parks, military installations, etc) carry a "reserved" water right that takes precedence over any state-sanctioned water appropriation. Rather than a specific quantity, the reserved water right guarantees a more open-ended "all water necessary to insure the original purpose of the reservation." In a similar way, the Indian tribes have a reserved water right that predates state appropriation and guarantees to them all water necessary to insure their adaptation from nomadic cultures to "agriculture and the arts of civilization." This right was first articulated in the Supreme Court decision, Winters v. US (1908) and is known as the Winters Doctrine. Indian reserved water rights are superior to state-sanctioned water rights, and for that reason, they have caused some havoc in the west. The decision Arizona v. California (1963) reiterated the Winters Doctrine and took steps to determine what quantity of water the tribes are entitled to. The decision stated that tribes might well claim all the water necessary to irrigate the "practicably irrigable acres" of the land reserved to the tribe by treaty. That is an enormous quantity of water for the arid west. More recent decisions have extended the reserved right to include not only surface but also groundwater. Still, few tribes have moved to assert their claim to a specific quantity of water. To do so means "Quantification;" that is, to put an exact "acre foot" measurement to the given tribe's water appropriation. Quantified totals then fall under state law. For the tribes this means sacrificing what is most valuable about the Indian reserved right--its open-endedness. Tribes do not want to limit themselves when they do not know what the future needs of the tribe will be. Also most tribes are reluctant to sacrifice their sovereignty and be subject to a state appropriation. This leaves states and water basin management authorities with no way to plan water allocation. The tendency has been to "plan the tribes out of existence." Nationally, seventeen tribes have quantified their reserved right because of overwhelming pressure from environmental overuse by non-Indians, including corporate agriculture and extractive industries. While quantification can be determined in court, these tribes quantified their Winters right through negotiation. Negotiations may eventually take the form of compacts between the tribe, the state, and the federal government. Compacts are "treaty-like" in that they are sovereign-to-sovereign documents, and in addition to quantifying the tribe's water right, a compact may include settlements involving past wrongdoing by any of the participants; resolution of taxation questions; and/or any ongoing litigation. Compacts can also provide for water marketing: intra-basin water sales of tribal surplus water. Marketing does not fall under the purview of the original Winters Doctrine; arguably sales do not fulfill the original purpose of the reservation. Water marketing is an enormous incentive for tribes to quantify. Tribes can and will litigate their reserved water right. Some attorneys argue that tribes within the boundaries of Oklahoma do not have a reserved water right, asserting that the reserved right was lost with the land base during the allotment era (1887-1902). While no court has determined the nature of the Winters right on a non land-based reservation, Oklahoma tribes have a compelling case. Tribes continue to own some communal "trust" land with attending Winters rights. Also the high court and Congress have designated the old reservations, for legal purposes, be considered "Indian Country," potentially imbuing a Winters-based claim. In addition, in U.S. v Powers (1939), the high court extended the Winters right to individual Indian allottees. Claims also can be asserted under Section 7 of the General Allotment Act of 1887 as well as Section 1 of Oklahoma's Enabling Act. All Oklahoma tribes including those of western Oklahoma, have a strong case should they litigate. In addition to Winters-based claims the Choctaw and Chickasaw by virtue of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, the Curtis Act, and the stipulations of the Louisiana Purchase have already claimed 90% of Oklahoma's surplus water. For these tribes the issue of Indian reserved water rights has already come to the fore when Texas approached the state to buy surplus water from southeastern Oklahoma. The Chickasaw and Choctaw were involved in those compact negotiations. Due to public outcry over the transaction, the Oklahoma Legislature has imposed a moratorium on water sale transactions. The two tribes have also been involved in recent Oklahoma legislative attempts to restrict basin-to--basin sales within Oklahoma. Any Oklahoma-imposed restrictions may well begin protracted litigation by one or several of the tribes. Urgency, for the tribes within the boundaries of Oklahoma, has been thus far mitigated by the lack of severe water shortages and the confused system of water appropriations. Legally, Oklahoma is a dual-system state. Unlike most western states, Oklahoma still maintains riparian water rights. These rights allow for "reasonable use" by all property owners. Confusingly, Oklahoma also recognizes prior appropriation, or the "first in line, first in right" water law of the arid west. In this chaotic situation, the nature of Indian water rights is uncertain. In times of shortage, riparian rights stipulate that all users, including Indians, diminish use. Under a system of prior appropriation, water use is diminished in the order in which it was appropriated. Winters rights, under a system of prior appropriation, predate all non-Indian state water appropriations. In times of shortage, Winters rights are recognized as superior. It is only a matter of time and diminishing water resources before the tribes pursue these superior rights. Wisdom dictates that the State begins to organize some response to inevitable tribal demand for a share of Oklahoma's water resources. Other western states, more arid in nature, have been forced to deal with Indian reserved water rights for some time. Notably in its efforts to plan water resources more coherently, the State of Montana formed a permanent body in 1979: the Reserved Water Rights Compact Commission. The Oklahoma Water Resources Board has formally acknowledged Indian reserved water rights, and in its 1995 study, the Citizen's Advisory Committee to the Oklahoma Council on Water Policy recognized the Indian water right, recommending to the Water Resources Board a cooperative resolution for water-related issues. The Committee urged the formation of a mutually acceptable negotiation system to resolve future water rights issues. In the ensuing eight years, the urgency of the Citizen's Advisory Committee's recommendation has only increased. As overuse of water resources continues, no doubt the status of the reserved right for the tribes within the boundaries of Oklahoma will be clarified either through litigation or negotiation. It is not in the interests of the State of Oklahoma to pursue a course that allows the tribes to be "planned" out of their water rights, nor is it in the interests of the State to litigate each tribe's reserved water right. The State should include Indian reserved water rights negotiations in a comprehensive approach to water allocation. In matters of tribal water allocation, the State of Oklahoma's inaction is an adverse action for both tribal and state interests. Selected Bibliography Ambler, Marjane. Breaking the Iron Bonds: Indian Control of Energy Development. Lawrence: University of Kansas, 1990. Getches David, ed. Water and the American West. Boulder: University of Colorado Natural Resources Law Center, 1988. Hundley, Norris. Water and the West: The Colorado River Compact and the Politics of Water in the American West. 1975. McCool, Daniel. Native Water: Contemporary Indian Water Settlements and the Second Treaty Era. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2002. Shurts, John. Indian Reserved Water Rights: The Winters Doctrine in its Social and Legal Context, 1880s-1930s.Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000. Sly, Peter W., Reserved Water Rights Settlement Manual. Washington, D.C., 1988. Veeder, William F. "Winters Doctrine Rights: Keystone of National Programs for Western Land and Water Conservation and Utilization," Montana Law Review 26: 149-172. Selected legislation and legal decisions Arizona v. California, 373 U.S. 546 (1963). Cappeart v. U.S. 426 U.S. 128 (1976). United States v.Thomas R.. Powers, 305 U.S. 527 (1939). Winters v United States, 207 U.S. 564 (1908). U.S. 24 Stat., 388. The General Allotment Act Act of Congress, June 16, 1906, 34 U.S. St. at Large, pp. 267-278 |

Tribal enterprises: Seeking a level playing field 2003-12-14 By Mickey Thompson Educating Oklahomans and all Americans on the potential impacts of federal and state Indian policies is the primary goal of a coalition of business and property rights advocates called One Nation Inc. One Nation -- a name taken from the final sentence of the Pledge of Allegiance -- includes thousands of individuals and companies in energy, agriculture, retailing, manufacturing and grass-roots organizations. Among the state and federal issues most important to One Nation: It is legal for tribal businesses to sell goods to tribal members without local, state and federal taxes. It is illegal for tribal businesses to sell goods to non-tribal members with no tax or reduced tax. Unfortunately, the law is not enforced in Oklahoma. As a result, the state is losing hundreds of millions of dollars a year in sales and excise taxes. And hundreds of non- tribal businesses are unable to compete with their subsidized tribally owned competition. Tribal governments can attain federal authority for water and/or air quality programs. Thirteen Oklahoma tribes have applied for such programs to the Environmental Protection Agency. Dozens of tribes in other states have implemented their own regulatory regimes, superseding local, state and federal laws, most with disastrous results for non- tribal businesses and property owners. We are concerned a regulatory patchwork across Oklahoma would drive away investment capital and stymie economic growth. Plus, some Oklahoma tribes are attempting to change federal law so their tribal governments may claim reservation status for former Indian reservations here. This could give tribal governments jurisdiction over non- tribal businesses on non-tribal lands in 67 of our 77 counties. We recently read in The Oklahoman about the explosive growth of Oklahoma tribes' political contributions. We encourage tribal leaders and members to become involved in politics. But what these stories haven't mentioned is that tribal governments aren't playing by the same rules as the rest of us. State law prohibits corporate contributions and requires contributors and contributions be reported to the Ethics Commission. Indian tribal governments do neither. It appears tribes are giving government money (tax dollars) or corporate money (funds from tribal enterprises). Neither should be allowed. Oklahoma has the worst record among states that have negotiated compacts with tribes. This is testament to the tremendous political power wielded by Oklahoma tribes. Additionally, we believe the process of compacting with tribes in Oklahoma is unconstitutional. We believe compacts, much like treaties, must be negotiated by the executive branch and must be ratified by the Legislature. There are many other important issues, such as removal of millions of dollars of property from county tax rolls as it is purchased by tribal governments, the protection of land and water rights for landowners and municipalities, and the problematic nature of doing business with tribal enterprises that can't be sued (sovereign immunity). No one claims the tribes don't provide benefits. On the contrary, an estimated $1.5 billion flows annually from Congress to the tribes for programs on housing, nutrition, education, etc., for Indians. No one should dismiss the fact tribes have created job opportunities in the delivery of government services and economic development. We believe the tribes can do this without inherently unfair tax, regulatory and other advantages that distort the marketplace. We believe these issues deserve public attention, debate and resolution. Thompson is president of the Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association and co-founder of One Nation. |

Seeking Statehood Tribes' Requests Could Pose Headaches 10/06/2003 NOTE: EDITORIAL -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- THIRTEEN American Indian tribes in Oklahoma are asking the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to treat them as individual states. It's a move that would give the tribes more control of environmental regulation on their lands, but also could lead to major headaches down the road. Tribal officials call it a "self-governance issue." Cherokee Nation spokesman Mike Miller says the request is "designed to let Native Americans in the tribes that have land in Oklahoma have a voice in how the environment is regulated or in keeping the environment in that area clean." It's understandable that tribes would want to be able to regulate the environmental goings-on on their land. But part of what makes us uncomfortable is that Oklahoma is home to 39 federally recognized tribes, and they're located in just about every corner of the state. It's conceivable each could have different standards as to what's allowable on their lands, some more stringent than others, and that would create a puzzling and daunting maze of regulations. Here's an example cited by Mickey Thompson, head of the Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association: A small tribe in New Mexico that was granted regulatory control over its reservation established its own standard for water quality on the Rio Grande. The standard was 3,000 times tougher than the regulation in Albuquerque. The city has since spent $60 million trying to clean up the river. Oklahoma tribal officials say it wouldn't make sense to pass the kinds of strict rules that would discourage business growth, especially since the tribes themselves need such growth. "The Chicken Little response that the sky is falling has no rational basis," says Cherokee Chief Chad Smith. Perhaps not. But the idea of a potential business or industry having to deal with any number of varying regulations, even if they weren't overly strict, could still prove discouraging enough to cause them to look elsewhere. This is an idea that makes more sense and might be more workable in states where tribal control is limited to reservations. Oklahoma's Indian lands are spread far and wide Thompson says historical reservation boundaries cover more than four-fifths of the state. Monty Matlock with the Pawnee Nation says he would prefer to see a more uniform state standard that includes input from the tribes. "But that's not going to happen any time soon," he said, so meanwhile tribes must have the power to enforce environmental standards. We're concerned about ever getting the lid back on this can of worms once it gets opened, if it does. |

December 11, 2003 West Texans Sizzle Over a Plan to Sell Their Water By RALPH BLUMENTHAL LPINE, Tex. Angry West Texans and some state officials are demanding a halt to a deal that allows a group of politically well-connected Midland oilmen to tap the desert and sell billions of gallons of water from the state's public reserves. The venture was advancing without announcement or competitive bidding by the powerful Texas General Land Office, which controls 20 million acres of public lands and the liquids and minerals beneath them. The agency has never licensed private sale of its water. The eight-man water partnership, Rio Nuevo Ltd., seeks to be the first, pumping out and selling some 16 billion gallons a year to municipalities and ranchers in drought-parched far west Texas, where many people fear that their own wells could go dry as a result. Since last year, people involved in the matter say, the land office steward of a nearly $18 billion permanent school fund to benefit public education has given an exclusive hearing to Rio Nuevo, prodded by the speaker of the Texas House, Tom Craddick, Republican of Midland. The proposed deal has raised a ruckus in this remote town of 6,000 and its Big Bend country sister communities Marfa and Marathon. Since the news leaked out two months ago, lawmakers and others have called on the land commissioner, Jerry Patterson, to avoid any action pending further examination. Adding to the furor are accounts that Rio Nuevo sought to deliver its water by sending it down the Rio Grande a plan the state's agriculture commissioner called "cockamamie" and to pay the state 20 cents an acre for water rights to 646,548 acres in six counties, a yield to the schools of about $129,000. The company now disavows that figure. The proposed scope was cut to 355,380 acres in four counties at fees Rio Nuevo now says would yield the schools about $7 million a year. The company also says it plans to invest $350 million in water pipes and pumps. Who would buy the water and at what cost is not yet clear, though a likely customer could be the City of El Paso. But Adrian Ocegueda, a spokesman for Mayor Joe Wardy of El Paso, said that studies of the impact on the water level should precede any deal. A bipartisan State Senate subcommittee was formed to look into the matter, its five members writing Commissioner Patterson that "concerns remain about the lack of a formal process by which this, and any future proposals, will be evaluated and decided upon." Mr. Patterson and Rio Nuevo representatives sat through a heated meeting with 500 residents in this Brewster County seat on Dec. 2 and said a 90-day public comment period would precede any action. At the meeting, John King, superintendent of Big Bend National Park, warned that the water plan "could cause irreparable harm." A shortage of water outside the 800,000-acre park, Mr. King said after the meeting, could send wildlife streaming into it, disrupting a delicate balance. Mayor Oscar Martinez of Marfa said he had seen several springs go dry. The water deal, he said, should "not even be contemplated." By Texas law, unless a water district has been formed, landowners control the water beneath their property and can draw it out even if that depletes a neighbor's supply. This is known as the rule of capture, or "the biggest pump wins." Asked why the talks with Rio Nuevo had not been announced at the time, Mr. Patterson said, "We don't announce a lot of things under consideration." He confirmed that discussions about the lease had been held out of the public eye by the three-member board on which he sits. "We were cautious," he said. "We had never done this before." The water deal has the region on edge. It has set Mr. Patterson, a former state senator, against the agriculture commissioner, Susan Combs, a rancher and fellow Republican who said Rio Nuevo's plan grew out of a "cockamamie idea" sending water down the Rio Grande, where much of it could evaporate. Though big oil entrepreneurs, including T. Boone Pickens, have bought water-mining rights from public conservation districts and private land owners, the state has never opened its water to commercial marketing. But growing demand requires such sales, Mr. Patterson said. He said he would also consider sales of water under prisons, parks and other state property, just as the land office now leases rights to oil, gas, minerals and wind power. "The big question, the only question, is how much water is there, is there enough to export without doing harm to the local community?" Mr. Patterson said at the Alpine meeting. But Mr. Patterson and Rio Nuevo said they could afford to survey the supply only after a lease was signed. Mr. Patterson also said the land office lacked the money to mine and sell the water itself, though it is preparing to buy a water mining and sales business in Central Texas. He said that because the land office had no track record for letting a water contract, the first one would have to be awarded without bidding. Local people have turned out in record numbers to protest. "We're already taking more than the skies are putting back," said Tom Beard, a rancher who heads the Far West Texas Regional Water Planning Group. "The only reason they got this far," Mr. Beard said of Rio Nuevo, "is they're very politically plugged in." An analysis by Texans for Public Justice, a watchdog group, shows that six Rio Nuevo partners gave a total of $83,136 to Republican state candidates in 2001 and 2002 the bulk of it, $72,886, from Gary Martin, an oil investor and businessman. Mr. Martin declined to answer questions. Another partner, Roger Abel, a retired president of the Occidental Oil and Gas Corporation, said the project would prove publicly beneficial, taking water "from Texas for Texans" over a wide area. A third partner is Steve Smith of Austin, founder of Excel Communications, who spent about $4 million buying the hamlet of Lajitas near Big Bend in 2000 and who has invested some $60 million more to make it a luxury resort. Mr. Smith did not return a call but Mr. Abel said he was responding on his behalf. Other Rio Nuevo partners include Kyle McDonnold, a Midland lawyer, and four partners in a Midland oil exploration company called Falcon Bay Energy: Mike Ford, Anthony Sam, Robert Canon and Steve Cole. Mr. Canon said that before he and Mr. Cole founded Rio Nuevo, another Midland company, Mexco Energy, had bought an interest in a Falcon Bay oil and gas projects. Mr. Craddick, the House speaker, is a Mexico director, but Mr. Canon said that Falcon Bay and Rio Nuevo were separate entities and that Mr. Craddick had nothing to do with Rio Nuevo. Mr. Craddick, too, said through a spokesman that he had no connection with Rio Nuevo. But he did not dispute accounts that he had urged Mr. Patterson and David Dewhurst, the land commissioner at the time and now the state's lieutenant governor, to meet with Rio Nuevo partners. Ms. Combs, the agriculture commissioner, said that around April 2002, Mr. Martin approached her with an idea of marketing state water via the Rio Grande. It was folly, she said, because sending water into the river would entail large losses from evaporation. Not long afterward and at the behest of Mr. Craddick, Mr. Dewhurst said, he met with Mr. Martin to discuss the project. Mr. Dewhurst, who was running for lieutenant governor, said he later returned a contribution from Mr. Martin when he learned the oilman had an issue pending before him as land commissioner. "I thought it was a terrible idea," Mr. Dewhurst said of the proposal. Mr. Patterson said that at Mr. Craddick's urging, he, too, began meeting with the Rio Nuevo partners, even before he succeeded Mr. Dewhurst in January. Then, in May, as the legislative session wound down, the Texas House and Senate passed a bill that would allow the Rio Grande watermaster to put into the river "privately owned water" for delivery to clients and directed the state's Commission on Environmental Quality "to expedite any application for a permit" to carry out the act. Mr. Dewhurst said he remembered Rio Nuevo's pressing for such a bill, but said he did not focus on it during the session. Mr. Craddick's spokesman said the speaker had nothing to do with the bill. Val Clark Beard, the county judge of Brewster County and its top-ranking official, was skeptical. "It was widely perceived as the speaker's bill," she said. "Unusual things get done at the end of the session." |

Ignoring facts on water proposal Gov. Frank Keating 02/06/2002 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- IT'S unfortunate that Mickey Thompson ("Your Views," Jan. 23) chose to ignore the facts concerning the potential sale of excess Oklahoma water to Texas. His concern that any such sale might occur by my action without legislative input could have been allayed by his simply reading the available material. First, the draft - and it is just a draft, subject to additional negotiation after appropriate input - of the compact with the Chickasaw and Choctaw nations specifically provided that not only would the compact itself be subject to legislative approval but that any sale of water - and each and every subsequent proposed sale of water, if any - would be subject to separate approval by the Legislature. In addition, state law specifically provides that the Oklahoma Water Resources board can't grant a permit for any use of water outside the state without legislative approval. Therefore, Thompson's concern that we need additional laws is unfounded and those additional laws are unnecessary, although I have no problem with redundancy if that is the Legislature's decision. I have consistently said that I would only support the sale of water to Texas if the rights of all Oklahomans were protected, that we were assured that only excess water was being sold and that we were getting a fair price. Texas negotiators failed to meet the fair price criterion and the discussions were broken off. As a result, we won't know whether the contract with Texas would have provided for the kinds of safeguards that I could have supported and submitted to the Legislature. Thompson and members of his Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association are content to produce and sell oil and gas for out-of-state use. Unfortunately, they choose to join those who demagogue a potential sale of water - a renewable resource that's currently being grossly wasted. It's a sad day when honest debate is obscured by those who choose to ignore the facts and buy into scare tactics. |

Click here to add your text. |

Oil group criticizes Cherokees - Producers say lobbying efforts met with threats of retaliation Chris Casteel 10/15/2002 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- WASHINGTON - The Cherokee Nation is threatening to impose new regulations and taxes on oil and gas producers because the industry has stalled action on federal legislation that would change the way drilling leases are granted on restricted American Indian land, the head of the Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association charged Monday. Mickey Thompson, executive vice president of the trade group, said he obtained a copy of a document that outlines actions the Cherokee Nation might take to retaliate against those who have raised concerns about the bill, which is pending in the Senate. The document includes a line that says: "Threaten tribal regulations over oil and gas access, accounting, taxation, etc. Prepare tribal law to regulate and tax producers." Thompson said the association no longer will negotiate on the bill. Sen. Jim Inhofe, R-Tulsa, held up consideration of the legislation two weeks ago when oil and gas producers complained about the possible effects. Since then, Inhofe's staff has been working with the various groups trying to negotiate compromises. "If they want to threaten us with special taxes and regulations, they're a sovereign nation and they should just get with it," Thompson said. Mike Miller, a spokesman for the Cherokee Nation, said he did not know who drafted the document obtained by Thompson. He said a number of strategies had been discussed by tribal leaders to get the bill passed. "Apparently some ideas were put on paper," Miller said. "We followed through with the ones we thought were good, which was taking the high road." Miller said tribal officials have avoided personal attacks and have focused exclusively on trying to satisfy the objections raised by oil and gas producers and the Oklahoma Corporation Commission. The threat of new taxes and regulations "is not the policy or actions of the Cherokee Nation," he said. "The OIPA has publicly attacked a bill that has been in the works for several years, right on the eve of its passage, with very personal attacks on the chief," Miller said. The legislation, House Resolution 2880, was approved by the House in June and appeared headed for easy passage in the Senate. It would remove Oklahoma district courts from transactions involving restricted land controlled by members of the Five Nations - the Cherokees, Chickasaws, Creeks, Choctaws and Seminoles. The bill was authored by Rep. Wes Watkins, R-Stillwater. The Bush administration and Gov. Frank Keating's office have studied it and endorsed it. Members of the tribes testified before a Senate committee last month that no other tribe in the state or nation must go through a state court process to sell or lease land. The Bureau of Indian Affairs negotiates and approves transactions for other tribes, but a series of laws, the last in 1947, put the Five Nations' land affairs in state court. Tribal leaders say the oil and gas leasing aspect of the legislation is a relatively small concern that would affect few leases in eastern Oklahoma. They say the biggest benefit from the BIA's involvement would be the legal help in settling probate issues. "This is not an oil bill," Miller said. "This does not affect the oil industry much." Thompson said the changes would effectively shut down oil and gas exploration on those lands because of the bureaucratic hassles involved. Oklahoma Corporation Commissioners Denise Bode and Bob Anthony also have raised concerns with the legislation because of the oil and gas provisions, and because of other matters, such as electricity transmission, regulated by the panel. The document obtained by Thompson suggests that Bode, a Republican running for attorney general, would be the target of a public relations campaign that portrays her as "anti-Indian" and using her position to "pander to oil and gas interests." Bode attended a negotiating session two weeks ago and said she was trying to understand its reach and impact. She and Thompson have said they were unaware of the bill's implications until last month, though supporters say it has been in the works for years. The House passed similar legislation two years ago, but it wasn't taken up by the Senate. The document that angered Thompson also outlines grass roots efforts to persuade Inhofe and Sen. Don Nickles, R-Ponca City, to push the bill to passage, and "intelligence gathering" steps to get information about Bode and oil and gas producers in the state. Some of the tasks are assigned to members of the Cherokee Nation staff. Thompson said negotiations on the bill had not been friendly but had not been tense or "ugly" either. He said the document "sort of hit us in the gut. We thought we'd be able to negotiate very legitimate concerns." Miller said the Cherokee Nation was ready to address any specific concerns the association has. "They don't raise issues," he said. "They raise negativity and throw nonissues into the mix." |

.HOME |